| BEFORE II W.W. | II W.W.

|

AFTER II W.W. |

| UPDATED MAR 2024 | ME - CONTACT |

|

|

DOUGLAS SBD-5 DAUNTLESSJAEGER LECOULTRE CHRONOFLITE |

|

|

|

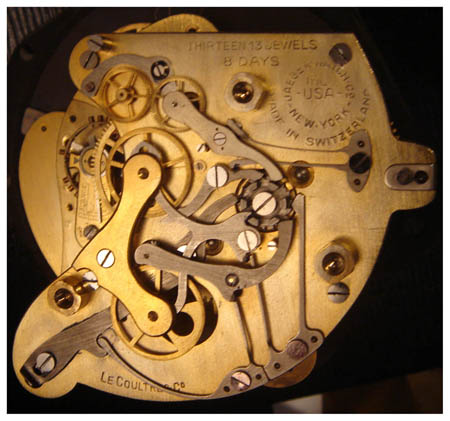

THE CLOCKIn 1930 LeCoultre designed the first CHRONOFLITE, a clock for airplanes with double chronograph, the “Air Corps”, predecessor of USAF, bought to Jaeger of New York this clock, it was the first clock with “elapsed time”.It was the movement more widely used before WW II, Smith from England mounted a CHRONOFLITE movement just with elapsed time, and the Russian Wostok copied the movement without license and equipped from the Policarpov I-16 Rata, up till the MIG 15. It was also used in racing cars of the 30 and 40 decades.The first models of Chronoflite was built with a 12 hour DIAL and without “civil date”. All of them have 13 jewels and only one mainspring barrel for eight days.The main drawback of this watch is that it is wound in the counterclockwise direction. This means that it was frequently broken when people wound it in the wrong direction, which is the natural way to do it.Another drawback of this model is that the chronograph minute counter rotates counterclockwise. Both of these issues were fixed in the design of the Elgin Hamilton 37500. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

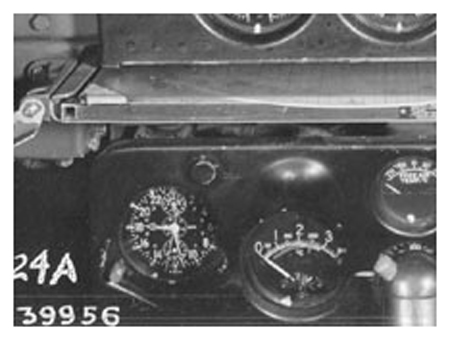

THE PLANE The Dauntless was the only U:S: aircraft to participate in all five carrier versus carrier engagements in the Pacific. The first deliveries to the US NAVY in 1940, in spite of its laking in range and engine power, its vulnerability and exhausting to fly, and in spite of it wings cant be fold, it become a legendary and most successful shipboard dive bomber of all time. It had more to do with the success in the Coral Sea battle and Midway where the Dauntless credited four Japanese carriers and one heavy cruiser than with the aircraft itself. The original NAVY contract called for 57, this number increased to 500 after the attack on Pearl Harbor. THE COCKPIT The most striking feature of the cockpit is the map table, which folded down from the middle of the instrument panel, as seen in the photographs. Due to this table, the flight stick was too short. Pilots are often seen in photographs leaning forward to reach the stick, and it was very difficult to apply G-force in this position. The table made it difficult to see the lower instruments even when it was folded up. In addition, the instrument panel was limited on each side at the top by the 50mm cannon breeches. On the right side of the cockpit were the levers for the landing gear marked W, the flaps marked L, and the dive brakes marked D. More than one pilot lowered the landing gear instead of the air brakes when starting an attack. It was necessary to be careful not to make a mistake.

THE DIVEThe dive was iniciate 4 NM from the target, starting at 20.000 - 15.000, then pushing the stick forward in a 70º dive, at full dive speed the dropped was at 240 Kts. Air resistence buffeted the plane and deafened the earing, with one eye in the bomb scope and the other in the speed and mainly in altimeter, 1.500 ft was needed for a normal 6 to 8 g´s pull out, plus 1.000 ft for stay above bomb fragments. Once the bomb was released the pilot felt a jolt and the bomb pivoted downward behind the plane to clear the propeller. All dive took aproximately 40 second. The procedure for a dive was: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

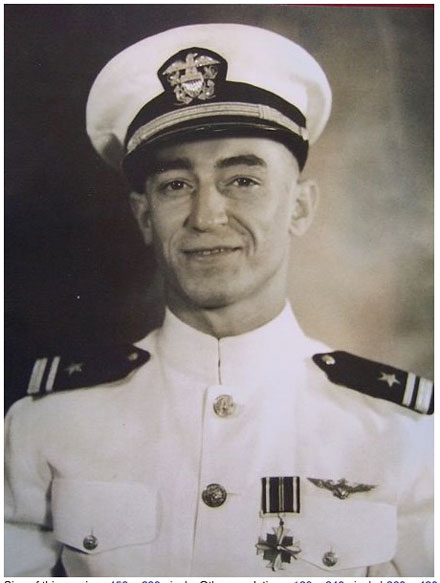

N. JACK "DUSTY" KLEISS |

|

|

Dusty served in Scouting Squadron 6 from the USS Enterprise. He saw action in the Battle of the Marshall Islands and actively participated in the Battle of Midway, achieving direct hits on two Japanese carriers, Kaga and Hiryu, and the cruiser Mikuma.. This easy-to-read book, "NEVER CALL ME A HERO" by Timothy and Laura Orr, recounts Kleiss's story with the simplicity, sincerity, and humility of a true hero. While his role in the Battle of Midway is the most significant of his aeronautical career, I find the following passage from the Battle of the Marshall Islands particularly gripping.

Flying in the first three-plane section, directly beside Best, I had the first pick of targets. As we sped towards the "push-over" point, I turned and saw the three Japanese fighters swooping down from above my right front. Engaging my split flaps, I slowed my plane rapidly, causing all three enemy fighters to overshoot me. One Japanese plane flew critically close. I can still recall the ear-splitting WHOOSH !! of its passage! Sometimes, when I close my eyes, I can even visualize the goggled face of the pilot looking up at me. **Safe for the moment, I followed Best into his dive, braving a barrage of anti-aircraft fire..." |

|

|

|

|

GO TO - CLOCKS FOR SALE |

GO TOP OF THE PAGE |

HOME |